The Intimate Documentary "Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child"

Forever remembered as one of the art world’s brightest—and fastest burning—stars, Jean-Michel Basquiat began his meteoric rise to fame in the late 70s, when he ran away from home to live on the streets of New York. Branding himself as a graffiti artist under the mysterious moniker “SAMO©” (a portmanteau of “Same Old”), he soon attracted the city’s counter-cultural royalty, collecting friends such as Debbie Harry, Keith Haring, Glenn O’Brien and Andy Warhol, before turning to painting and storming galleries in New York and Los Angeles with his brightly hued, neo-expressionist works. Basquiat produced thousands of artworks in his short life, dashing off his poetry-infused canvases at a hair-raising pace, but footage of the artist himself has been hard to come by since his death in 1988. Director Tamra Davis, who met and befriended Basquiat when he visited LA to exhibit at the Gagosian gallery in 1983, was one of few to document the artist during his lifetime. Profoundly affected by his death, Davis hid her reels for two decades. But in 2005, prompted by a friend working on MOCA’s Basquiat retrospective of that year, Davis returned to her 80s footage to create a short, 20-minute tribute to the artist. “Everybody at the museum flipped out because the footage I had was incredibly rare,” she says. “They said, ‘This is so important! You can’t just keep it in your closet––you have to show this film.” So Davis developed the short into a feature-length documentary with Arthouse Films, Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child, seeking out Basquiat’s contemporaries, friends and admirers, from his longtime girlfriend Suzanne Mallouk to artist Julian Schnabel and early hip-hop maestro Fab Five Freddy. The film documents Basquiat's transformation from slouching street kid into international art world darling, accompanied by graphic animations by artist Shepard Fairey and a soundtrack from Beastie Boys Adam Horovitz and Mike Diamond and Manhattan-based composer J. Ralph. Today’s clip is an exclusive preview of the film, which in association with NOWNESS, had its New York premiere at MoMA during the Tribeca Film Festival.

Friday, April 30, 2010

Thursday, April 29, 2010

SAVE THE DATE: MAY 23, 2010

"Greater New York 2010" at P.S.1

May 23, 2010 - October 18, 2010

P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center

22-25 Jackson Avenue

Long Island City, NY

22-25 Jackson Avenue

Long Island City, NY

Greater New York, the third iteration of the quintennial exhibition organized by MoMA PS1 and The Museum of Modern Art, showcasing some 68 artists and collectives living and working in the metropolitan New York area, will open at MoMA PS1 on May 23 and run through October 18, 2010. The 2010 exhibition will not only present recent work made within the past five years, but also will foster a productive workshop where artists will be invited to experiment with new ideas within MoMA PS1's building for the duration of the exhibition. Greater New York is organized by Klaus Biesenbach, Director of MoMA PS1 and Chief Curator at Large at The Museum of Modern Art; Connie Butler, The Robert Lehman Foundation Chief Curator of Drawings, The Museum of Modern Art; and Neville Wakefield, MoMA PS1 Senior Curatorial Advisor. Covering a full range of practices and mediums, the artists in Greater New Yorkare inspired by living in one of the most diverse and provocative centers of cultural activity in the world. The exhibition centers largely on the process of creation and the generative nature of the artist's studio and practice. A number of artists are being commissioned to work in residence in MoMA PS1's gallery space to shoot photographs and video, rehearse and realize performances, and stretch the notions of sculpture, painting, photography, film, and video-making. The Greater New York 2010 curators selected artists through studio visits, review of recommendations, mailed submissions, and through Studio Visit, a new initiative on www.MoMAPS1.org that invites artists to present their artwork and studios online. Over 750 Studio Visit submissions were reviewed by the curatorial team.

For more information and a list of artists please visit http://www.barbarabalkin.com and select "SEE"

Wednesday, April 28, 2010

ANOTHER VICTIM

Art fabricator Carlson & Co., which gained fame by producing Jeff Koons’s stainless-steel “Balloon Dog,” is closing. Company founder Peter Carlson said it will be filing something “akin” to bankruptcy.

“The economic climate contributed very much to the condition we find ourselves in,” Carlson said in a phone interview. The company, based in San Fernando, California, was founded in 1971. It became one of the best-known resources for artists seeking to produce complicated, large-scale and frequently costly artworks. The firm fabricated some of the most technically challenging artworks created during the six-year rise of contemporary art prices which began in 2002. Besides Koons, Carlson was the producer of choice for dozens of top contemporary artists, including Doug Aiken, John McCracken and Charles Ray. The company probably won’t finish a number of projects. “Our ability to complete projects is limited,” Carlson said. The use of high-end fabricators like Carlson became increasingly popular in the past decade as billionaire art collectors hunted for pricey large-scale artworks to fill private museums and foundations. Carlson’s reputation rose along with the contemporary art market. The company was featured in a profile in the New York Times in 2007, the same year Artforum magazine devoted an issue to “The Art of Production.” At the time, the company was engrossed in solving Koons’s latest puzzle: the construction of a 70-foot-long replica of a 1943 steam locomotive, designed to dangle from a crane, outside the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The work was estimated to cost $25 million, according to the Times article. Peter Carlson is quoted comparing the Koons train to the scale of “major industrial pieces, like the Eiffel Tower.” The project is “still in the feasibility study phase,” said LACMA spokeswoman, Barbara Pflaumer.

Saturday, April 17, 2010

"EXIT THROUGH THE GIFT SHOP"

A still from "Exit Through the Gift Shop."

No, it's not a hoax -- but the British street artist's hilarious documentary is a head-spinning, wild ride. Sincerity always poses problems for the news media. Maybe the press has professionally inoculated itself with a vigorous blend of skepticism and cynicism, and maybe it's just grown ever more fearful of being punked by pranksters, celebrities and presidents. One can only wish the New York Times had viewed the Bush administration's call to war with half the caution with which it has approached "Exit Through the Gift Shop," the new documentary made (or presided over, or something) by the mysterious British street artist Banksy. Commentators for the Times, National Public Radio and elsewhere have become hypnotized by the question of whether this fascinating and often exciting film about the global rise of guerrilla art, Banksy's own career as a provocateur and the genesis of a sub-Banksy pop artist called Mr. Brainwash might itself be some kind of meta-fictional Banksy prank. I felt some of the same anxiety after first seeing "Exit Through the Gift Shop" a few months ago at Sundance, but I now think that reaction dramatically misses the point of the film. Banksy offers a heady and hilarious voyage through the underworld of contemporary art that poses all kinds of puzzlers about the role, meaning and context of allegedly subversive art in a consumer society. "Exit Through the Gift Shop" is of a piece with Banksy's murals and installations -- bending a London phone booth in half, hanging his own "Old Master" painting in the Tate Gallery, planting a dummy wearing an orange Gitmo jumpsuit within a Disneyland ride -- in many ways. It's both a work of art and a process, in which the subject and object of creation seem to trade places. It's meant to shift your perspective, both subtly and dramatically, no matter where you stand on the value of guerrilla art like Banksy's. Moreover, it's both a documentary that captures Banksy practicing his daring craft and an elaborate joke at his own expense that depicts him in an unexpected light. Narrated by Rhys Ifans in plummy, mock-BBC tones, "Exit Through the Gift Shop" begins as a story about would-be filmmaker Thierry Guetta, a strange little French émigré who ran a vintage clothing store in Los Angeles and whose cousin was the Paris graffiti artist known as Space Invader. (You can guess what his stencils look like.) Guetta began compulsively documenting his cousin's work with a video camera, and then moved on to other prominent street artists, including Shepard Fairey -- now famous for his iconic Obama images -- and finally, after a great deal of patience and detective work, the notoriously elusive Banksy. (According to his Wikipedia entry, Banksy is originally from Bristol, in southern England, and is about 35. His stencil work began to appear on the streets of Bristol and London around 2000.) But after Banksy and Guetta start hanging out, a peculiar exchange follows: The artist becomes the director, and the filmmaker becomes his subject. Banksy, who is seen in the film delivering wry expositions -- severely backlit, in a hoodie, with his voice masked -- came to realize that Guetta was unable or unwilling to make a coherent film out of all his footage, and took over the project himself. Encouraged by Banksy to put down the camera and create his own art, Guetta transformed himself into Mr. Brainwash -- at best, a miscellaneous repurposer of pop-culture images already adopted by other artists -- and succeeded beyond anyone's expectations. This film has many levels, but in no sense is it insincere, or an attempt to trick you. If anything, it's a rueful, comic exploration of what happens when artists like Banksy and Fairey, who have set themselves up as subversive opponents of the pretentious, big-money art establishment, see their own weapons used against them. Despite their rebel status, Banksy and Fairey are forthright about clinging to relatively old-fashioned ideas about artistic craft, training and vision. Somebody like Guetta, who lacks any art education or knowledge of art history, and whose aesthetic is mainlined from every prominent pop or street artist since Andy Warhol, threatens to undermine their entire raison d'être. To put it more directly: They're good and he isn't, but a whole lot of people apparently can't tell the difference. Banksy himself seems relaxed and even jovial about this. He has said he doesn't want to extend his own artistic career beyond its point of social or political usefulness, and the ultimate lesson of "Exit Through the Gift Shop" is exactly what its title implies -- that all the best ideas of all the most brilliant artists are ultimately rendered into more crap for sale. As Banksy's London dealer muses late in the film, on the subject of Mr. Brainwash: "Good for Thierry if he can pull it off. At the same time, the joke's on ... well, I'm not sure who the joke's on. I'm not even sure there is a joke."

Andrew O'Hehir

Salon.com

"Exit Through the Gift Shop" is now playing in New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco. It opens April 23 in Boston, Philadelphia and Seattle; April 30 in Atlanta, Baltimore, Chicago, Denver, Minneapolis, San Diego and Washington; May 7 in Indianapolis and Toronto; and May 21 in Austin, Texas, with other cities to be announced.

No, it's not a hoax -- but the British street artist's hilarious documentary is a head-spinning, wild ride. Sincerity always poses problems for the news media. Maybe the press has professionally inoculated itself with a vigorous blend of skepticism and cynicism, and maybe it's just grown ever more fearful of being punked by pranksters, celebrities and presidents. One can only wish the New York Times had viewed the Bush administration's call to war with half the caution with which it has approached "Exit Through the Gift Shop," the new documentary made (or presided over, or something) by the mysterious British street artist Banksy. Commentators for the Times, National Public Radio and elsewhere have become hypnotized by the question of whether this fascinating and often exciting film about the global rise of guerrilla art, Banksy's own career as a provocateur and the genesis of a sub-Banksy pop artist called Mr. Brainwash might itself be some kind of meta-fictional Banksy prank. I felt some of the same anxiety after first seeing "Exit Through the Gift Shop" a few months ago at Sundance, but I now think that reaction dramatically misses the point of the film. Banksy offers a heady and hilarious voyage through the underworld of contemporary art that poses all kinds of puzzlers about the role, meaning and context of allegedly subversive art in a consumer society. "Exit Through the Gift Shop" is of a piece with Banksy's murals and installations -- bending a London phone booth in half, hanging his own "Old Master" painting in the Tate Gallery, planting a dummy wearing an orange Gitmo jumpsuit within a Disneyland ride -- in many ways. It's both a work of art and a process, in which the subject and object of creation seem to trade places. It's meant to shift your perspective, both subtly and dramatically, no matter where you stand on the value of guerrilla art like Banksy's. Moreover, it's both a documentary that captures Banksy practicing his daring craft and an elaborate joke at his own expense that depicts him in an unexpected light. Narrated by Rhys Ifans in plummy, mock-BBC tones, "Exit Through the Gift Shop" begins as a story about would-be filmmaker Thierry Guetta, a strange little French émigré who ran a vintage clothing store in Los Angeles and whose cousin was the Paris graffiti artist known as Space Invader. (You can guess what his stencils look like.) Guetta began compulsively documenting his cousin's work with a video camera, and then moved on to other prominent street artists, including Shepard Fairey -- now famous for his iconic Obama images -- and finally, after a great deal of patience and detective work, the notoriously elusive Banksy. (According to his Wikipedia entry, Banksy is originally from Bristol, in southern England, and is about 35. His stencil work began to appear on the streets of Bristol and London around 2000.) But after Banksy and Guetta start hanging out, a peculiar exchange follows: The artist becomes the director, and the filmmaker becomes his subject. Banksy, who is seen in the film delivering wry expositions -- severely backlit, in a hoodie, with his voice masked -- came to realize that Guetta was unable or unwilling to make a coherent film out of all his footage, and took over the project himself. Encouraged by Banksy to put down the camera and create his own art, Guetta transformed himself into Mr. Brainwash -- at best, a miscellaneous repurposer of pop-culture images already adopted by other artists -- and succeeded beyond anyone's expectations. This film has many levels, but in no sense is it insincere, or an attempt to trick you. If anything, it's a rueful, comic exploration of what happens when artists like Banksy and Fairey, who have set themselves up as subversive opponents of the pretentious, big-money art establishment, see their own weapons used against them. Despite their rebel status, Banksy and Fairey are forthright about clinging to relatively old-fashioned ideas about artistic craft, training and vision. Somebody like Guetta, who lacks any art education or knowledge of art history, and whose aesthetic is mainlined from every prominent pop or street artist since Andy Warhol, threatens to undermine their entire raison d'être. To put it more directly: They're good and he isn't, but a whole lot of people apparently can't tell the difference. Banksy himself seems relaxed and even jovial about this. He has said he doesn't want to extend his own artistic career beyond its point of social or political usefulness, and the ultimate lesson of "Exit Through the Gift Shop" is exactly what its title implies -- that all the best ideas of all the most brilliant artists are ultimately rendered into more crap for sale. As Banksy's London dealer muses late in the film, on the subject of Mr. Brainwash: "Good for Thierry if he can pull it off. At the same time, the joke's on ... well, I'm not sure who the joke's on. I'm not even sure there is a joke."

Andrew O'Hehir

Salon.com

"Exit Through the Gift Shop" is now playing in New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco. It opens April 23 in Boston, Philadelphia and Seattle; April 30 in Atlanta, Baltimore, Chicago, Denver, Minneapolis, San Diego and Washington; May 7 in Indianapolis and Toronto; and May 21 in Austin, Texas, with other cities to be announced.

Thursday, April 15, 2010

"RED" BY JOHN LOGAN

Alfred Molina and Eddie Redmayne in “Red.” Photograph by Steve Pyke.

Mark Rothko’s life was a series of abdications: from Russia, when he was ten; from his father, who died six months after arriving in Portland, Oregon; from Yale, after two years; and from life itself, when he committed suicide, on February 25, 1970. A fractious, hard-drinking, unhealthy, and unhappy soul, Rothko was a gourmand of his griefs. By contrast, his large, luminous abstract canvases—spectacles of subtraction of all subject matter, including the self—turned abdication into an art form. Rothko was the first to paint “empty” pictures. His blocks of floating iridescence were the public answer to Action painting; privately, they were also a kind of vanishing act. At a party where Expressionism was being discussed, Rothko leaned over to the art critic Harold Rosenberg and whispered, “I don’t express myself in my paintings; I express my not-self.” In John Logan’s “Red” (elegantly directed by Michael Grandage, at the Golden), Rothko (Alfred Molina) is onstage twenty minutes before the play begins. He’s in his studio, a vast cave of consciousness that, subtly designed by Christopher Oram, also suggests a sanctuary. Rothko sits in a blue wooden chair with his back to us, surrounded by unfinished canvases that are propped against the high, dingy walls; he is studying one of five huge murals that he’s been commissioned to do for the new Seagram Building. His first gesture, once the play begins, is to walk up to the painting and feel the canvas with the flat of his hand. Rothko is already well inside the painting; the success of Logan’s smart, eloquent entertainment is to bring us in there with him. For a month in 1949, Rothko went to the Museum of Modern Art to stand in front of Matisse’s “The Red Studio,” which the museum had newly acquired. Looking at it, he said, “you became that color, you became totally saturated with it.” Rothko turned his transcendental experience into an artistic strategy; his work demanded surrender to the physical sensation of color. “Compressing his feelings into a few zones of color,” Rosenberg wrote, “he was at once dramatist, actor, and audience of his self-negation.” Rothko escaped from the hell of personal chaos into the paradise of color. “To paint a small picture is to place yourself outside your experience,” he said. “However, you paint the large picture, you are in it.” Logan’s theatrical conceit is to introduce an assistant into Rothko’s solitude, an aspiring painter named Ken (the excellent Eddie Redmayne). Over two years, between 1958 and 1960, he becomes Rothko’s student, gofer, whipping boy, and sounding board. In teaching Ken how to look at his art, Rothko indirectly teaches us. It’s an exciting education. Logan’s dialogue is a sleight of hand; behind its wallop is a lot of learning. “Nature doesn’t work for me,” Rothko says at one point. “The light’s no good.” The play then demonstrates the point. Ken switches on the overhead white fluorescent lights, which flatten the canvas and break the painting’s spell. “You see how it is with them? How vulnerable they are?” Rothko says after he’s returned the room to its crepuscular glow. “People think I’m controlling: controlling the light; controlling the height of the pictures; controlling the shape of the gallery. . . . It’s not controlling—it’s protecting.” Pontifical, obsessive, opinionated, vain, arrogant, and brilliant, Rothko had a sour wit. “How’s business?” he used to say to artist friends. Logan sometimes appropriates Rothko’s epigrams (“Silence is so accurate”), but his own idiom is well wrought and delightful. He doesn’t just tell; he also shows, at one point having Rothko collaborate with Ken in mixing paint and priming canvases. As classical music blasts from the record player, they slather the paint over the canvas, a balletic, two-minute explosion of activity that deftly conjures what most plays about artists don’t: the exhilaration of the act. As Rothko, the strapping Molina burns up the stage. Head shaved, striding across the studio with his barrel chest thrust forward, he is all feistiness and creative ferocity. Even in silence, he exudes a remarkable gravity. He also makes a gorgeous fuss. “I am here to stop your heart, you understand that?” he bellows at Ken, in one of their arguments about painting. “I am here to make you think. . . . I am not here to make pretty pictures!” Is there any contemporary actor who can roar like Molina? His big torso is a boom box that turns his lacerating words into a force field. For instance, in a moment of inspiration, just as Rothko is about to wield his five-inch housepainter’s brush, Ken misguidedly answers a rhetorical question about what the painting needs: red, Ken suggests. “By what right do you speak? . . . Who the fuck are you? What have you done?” Rothko shouts, throwing packets of red paint at him in his fury. “You mean scarlet? You mean crimson? You mean plum-mulberry-magenta-burgundy-salmon-carmine-carnelian-coral? Anything but ‘red’! What is ‘red’?!” It’s a terrific moment, shrewdly conceived and terrifying to watch. Molina is withering and dangerous; his achievement is to suggest in Rothko’s obsession both the madness and the grandeur of a great artist playing for keeps. “Red” is built around a canard—that Rothko painted the murals for the Four Seasons restaurant, in the Seagram Building, which was still under construction when he accepted the rich commission. He didn’t. Rothko, who had strong feelings about the public display of his work—eight hundred of his paintings were unsold when he died—was under the impression that the murals would be displayed in the lobby of the prestigious new building. He “refused to deliver them when he learned that they would be placed not in the lobby but in an adjoining restaurant,” Rosenberg wrote. Nonetheless, it’s a good story and a good hook on which Logan hangs his scintillating discourse about Rothko and modern art. Rothko frequently refers to his paintings as tragic. In the shifting movement of red and black in the murals, Logan suggests Rothko’s encroaching darkness. “There’s only one thing I fear in life, my friend,” he says. “One day the black will swallow the red.” While the play hints at dark things to come, it doesn’t linger on them; Logan prefers to emphasize the manic bits of the painter’s depressed personality.

John Lahr

The New Yorker

Rothko’s Art Reflects Baltic Landscapes, Scars of Russian Youth

On April 23, the Garage Center for Contemporary Culture will open the first exhibition of work by the abstract painter Mark Rothko held in Moscow. The event at the exhibition space run by Dasha Zhukova, Roman Abramovich’s partner, raises a question: How much was Rothko affected by the decade he spent in Russia? Of course, Rothko (1903-1970) was a U.S. citizen, and a leading member of the New York School of Abstract Expressionist painters. He left Russian territory, never to return, in 1913 when he was 10. Yet there are reasons for thinking that Rothko’s art and imagination were deeply influenced by those early years. He was born Marcus Rothkowitz in the city of Dvinsk, which was then part of the czarist empire. It’s now the Latvian city of Daugavpils. His family was Jewish, but spoke Russian not Yiddish at home, a sign of their educated status. The culture at home was literary and liberal. Rothko recalled the family sitting shiva -- the Jewish mourning ritual -- when Tolstoy died in 1910. His older sister Sonia remembered that “we were very interested in literature, all of us.” They left behind a library of 300 books when they emigrated to the U.S. According to his friend Herbert Ferber, quoted in James Breslin’s biography, Rothko was “very strongly interested” in his “Russian background.” The stories he told about those early years were often dark. Rothko had a scar on his nose that he said was caused by the slash of a Cossack whip while he was being carried as an infant. Several times Rothko described hearing relatives talking about a massacre -- where and when he wasn’t sure -- in which Cossacks forced Jewish villagers to dig a mass grave for themselves in the woods. Rothko said that he’d been haunted by the image of that grave and was sure it had found its way into his paintings. His friends suspected this memory to be a fantasy, and no such incident seems to be recorded. True or not, Rothko, “a high-strung, noticeably sensitive child,” according to his brother Moise, grew up in an atmosphere of menace. There were no pogroms in Dvinsk, but there were Cossacks, anti-Semitic prejudice and mounting political violence. That’s a possible source for the darkness in much of Rothko’s work. It’s the landscape, not the persecutions, of Dvinsk/Daugavpils that may have influenced his euphoric, light- filled abstractions of the late 1940s and early 1950s. It’s a place of forests and wide horizons on the Daugava River. The winters are long, dark and hard -- Rothko remembered skating to school -- and in midsummer the sun only sets for three hours a night. In a poem, he associated heaven with a light shining through mist. To a fellow painter, Robert Motherwell, Rothko extolled the “glorious” Russian sunsets of his childhood. On a personal note, a few years ago I sailed off the Baltic coast of Latvia in July. Each night there was a spectacular display of reds, pinks, gold and purples in the sky, for hour after hour. It recalled one painter above all: Mark Rothko. As is always the case with great art, the sources of Rothko’s painting are numerous, complex and ultimately mysterious. One point that’s often forgotten, though, is that he grew up in a Northern land, close to the latitudes of the midnight sun.

“Mark Rothko: Into an Unknown World” opens April 23 and runs through Aug. 14 at the Garage Center for Contemporary Culture in Moscow.

Martin Gayford

Bloomberg News

Tuesday, April 13, 2010

ALTERNATE REALITY

Left: Work of Art host China Chow. Right: Work of Art mentor Simon de Pury with Work of Art judge Bill Powers.

WITH VERY FEW EXCEPTIONS—PBS’s Art:21 and the occasional British import—contemporary art is conspicuous by its absence from mainstream American TV. To some this might seem a rank injustice, but given the obvious pitfalls, it may equally represent a lucky escape. Arriving at the Paley Center for Media for a Wednesday evening preview of Bravo’s new reality series Work of Art: The Next Great Artist, I felt more trepidation than would have accompanied any insider event. How would the art world fare at the hands of producers who aimed to do for it, in the words of the cable channel’s Frances Berwick, “what we’ve done for fashion and food”? Would the featured artists (who are, of course, pitted against one another in the bankable manner of Project Runway, Top Chef, and RuPaul’s Drag Race) survive the presumed emphasis on pizzazz? And would the judges shed all credibility by association with this demotic form? Taking a seat (the crowd was split between journos and those who I took, by their relatively well-heeled appearance, to be industry types), I settled in for a screening of the hour-long first episode. Intimacy with the subject of such a program tends to make the viewer hypersensitive to the details of its construction, and such was the case here. Editing was staccato and manipulative, competitors seemed to have been chosen entirely for their looks (though the judges later denied this), and “reality” seemed very far away indeed as the familiar struggles of most artists were displaced by a hothouse fantasy of prestocked studios and Project Runway–style accommodations designed to spark rivalry from the get-go. The artists, competing for the mixed blessing of a solo show at the Brooklyn Museum (Artnet’s Walter Robinson later wondered how the show’s producers, Magical Elves, secured the venue—apparently they just asked), ran the gamut of stereotypes from untrained and overawed to world-weary and imperious, though most had their quirks. And while the majority were young and telegenic, there were one or two exceptions. The host was immaculate ’90s It Girl China Chow (additionally qualified for the role by having been “born into a family of collectors”); the “mentor” was auctioneer Simon de Pury (presumably Tobias Meyer had other commitments); and the judges were Jerry Saltz, Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn, and Bill Powers, fashion-forward proprietor of Half Gallery. Contributing a bit of real star power, executive producer Sarah Jessica Parker also made a brief appearance. As the competition’s first challenge—the artists were paired off and asked to make portraits of each other—rattled toward its conclusion (the usual dramatic “voting-off” shenanigans), I found myself paying less and less attention to the (overwhelmingly dire) work and more to compiling a list of sententious quotes: “Wall power, that’s what you want” (de Pury); “To you, it’s a portrait, but to no one else will it ever be a portrait” (Saltz); “I’m getting falling leaves, is what I’m getting off this” (Powers), and the definitive “There’s no excuse for a bad painting” (Saltz again). Also good for a laugh were token tough guy Erik Johnson asking de Pury—to bemused reaction—if he fancied hitting a strip club after the show; senior feminist Judith Braun clashing with junior sexpot Jaclyn Santos; and Chow’s chilling dismissal of the show’s first loser: “It’s been said that good art isn’t what it looks like but what it makes us feel. Your art didn’t make us feel anything.” Ouch. The Q&A that followed—host and judges, along with SJP and co-producer Dan Cutforth, were all present—was good-natured, perhaps because most questions came from TV folk astonished that a show about art could be anything other than “stuffy” (initially misheard by Saltz as “scuzzy”). Accessibility was stressed again and again, but while it would be po-faced indeed to ignore the show’s more amusing interactions, it was hard to avoid feeling that some valuable middle ground between fusty and trashy was being overlooked. And when the panelists were asked whether they had managed to find “the next great artist,” I think we can take that long, awkward pause—Saltz’s shit-stirring claim “I saw artists here that were better than artists in the Whitney Biennial” notwithstanding—as a probably not. Oh well. The tribe has spoken.

Michael Wilson

Artforum

Monday, April 12, 2010

ROBINS V. ZWIRNER LAWSUIT

Dealer David Zwirner has fired back in the lawsuit against him by one of America’s better-known art collectors. In papers filed last Monday in the Southern District Court of New York, he charged that he never made or violated a “first dibs” promise or one of confidentiality in a prominent art sale. His response further raises the question of whether the collector was essentially speculating on art, flipping it for profit and as a tax-break strategy. The lawsuit, Robins v. Zwirner et al., goes to the heart of the intricate workings of the art world in recent years. Whichever side wins, it throws a spotlight on the growth of a stratified collector caste system, the rise in the practice of flipping art for profit, the development of sophisticated tax strategies to aid in art trading—and the widespread inability of any art-worlder to keep their mouth shut for long. Lawsuits are rare in the art world, or at least they used to be. In recent months, however, there have been a spate of them. Lawyers, collectors and dealers say a couple of factors have come together to make it more tempting to sue: The boom in art prices has made art worth going to court over, and commonly sent emails create a paper trail that can make litigation easier. But most of all, the rising tide of lawsuits is about the recession. In boom times, “you figure it will all even out on the next deal,” said one art attorney. “But when times get tight, you go to court.” it’s a mark of the times. Craig Robins, the well-known Miami real estate developer, is charging in his lawsuit that he sold a painting by noted South African artist Marlene Dumas in 2004, with Mr. Zwirner brokering the deal. Mr. Zwirner paid him in both cash and other artworks, in what’s called a like-kind transaction in the Internal Revenue Code. Mr. Zwirner agreed to keep the sale confidential, according to the suit, because the sale would be something of an affront to the artist and might prevent Mr. Robins from gaining access to her other works. Then, Mr. Robins charges, Mr. Zwirner gossiped, and gossiped with a motive. He told Ms. Dumas of the sale. Not long after, Mr. Zwirner became Ms. Dumas’s primary representative, a coup for the art dealer, as she had a 2008 retrospective of her work at the Museum of Modern Art, among other achievements. Meanwhile, Ms. Dumas, Mr Robins said, does not want to sell him any more paintings, even though, with six to eight of her paintings in his collection, and many more drawings, he is one of her primary collectors. Further, Mr. Zwirner had agreed to put him at the top of the waiting list for her works, and did not honor that promise, he said. Mr. Zwirner declined to comment; a spokesman for the gallery said “there is no evidence to support” Mr. Robins’ claim—and there doesn’t seem to be much of a paper trail either to confirm that a legal contract existed, which Mr. Robins said he has a witness to, or to support the implication that Mr. Robins is collecting for profit. Indeed, Mr. Zwirner’s response to the suit, filed last Monday, raises the issue of “art speculation” and notes “Ms. Dumas does not want collectors to speculate in her works or flip them for profits’ sake.” He also essentially argues, somewhat surprisingly, that while confidentially is assumed during an art-world transaction, it does not extend beyond it. Mr. Robins counters that he is not a speculator. “In nearly 30 years of collecting over 1,000 works of art, I have sold perhaps 50 of them—and I have never been in a legal dispute with a gallery or over a work of art, until now.”

apeers@observer.com

Thursday, April 08, 2010

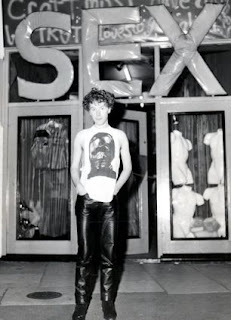

MALCOLM MCLAREN DIES: 1946-2010

“Stealing things is a glorious occupation, particularly in the art world.”

Malcolm McLaren

Malcolm McLaren, who has died from cancer at age 64, came to public attention in 1976 as the manager of the Sex Pistols, the punk band which he steered to fame and notoriety before their implosion barely two years later. McLaren is considered the godfather of punk and first made his name in 1971 when he opened a fashion boutique on the Kings Road in Chelsea with his partner, the designer Vivienne Westwood. With his unerring eye for publicity, he renamed the shop Sex. In 1975, he spotted a young punk called John Lydon who regularly hung around outside the shop. McLaren signed him up as the frontman of the fledging punk band he managed and the Sex Pistols were born.

When the band released God Save The Queen during the Queen’s Silver Jubilee in 1977, they became one of the most notorious acts in British music history. He once said: “I am a product of the Sixties. All I have ever felt is disruptive — I don’t know any other way.” McLaren always said punk was an attitude. "It was never about having a Mohican haircut or wearing a ripped T-shirt. It was all about destruction, and the creative potential within that. It turns out that the bankers may have been the biggest punks of all; they were making punk investments. I've always embraced failure as a noble pursuit. It allows you to be anti whatever anyone wants you to be, and to break all the rules. It was one of my tutors at Saint Martins, when I was an art student, that really brought it home to me." He said that only by being willing to fail can you become fearless. He compared the role of an artist to that of being an alchemist or magician. And he thought the real magic was found in flamboyant, provocative failure rather than benign success. "There are two rules I've always tried to live by: turn left, if you're supposed to turn right; go through any door that you're not supposed to enter. It's the only way to fight your way through to any kind of authentic feeling in a world beset by fakery. I believe in ideas, not products. Any survivor of a Sixties art school will tell you that the idea of making a product was anathema. That meant commodification."

ARE YOU FEELING LUCKY PUNK?

Tuesday, April 06, 2010

CHINA CONTEMPORARY ART SOARS

A painting by Liu Ye sold for HK$19.1 million ($2.5 million) at a Hong Kong auction, the most for a Chinese contemporary artist in two years, in a sign prices are returning to pre-credit-crisis levels.

Liu’s acrylic-and-oil “Bright Road,” showing a smiling couple with a flaming jet in the background, fetched an artist record. It was one of seven Chinese contemporary works that made $1 million or more at Sotheby’s sale, fueled by mainland and Indonesian money. During last year’s crisis, bidders passed on similar works offered at a third of yesterday’s prices. “Demand for the best Chinese contemporary artworks is back,” Eric Huang, a Taipei-based buyer and dealer, said in an interview at the auction. “Don’t be surprised to see prices match or even beat pre-crisis levels very soon.” Prices of top Chinese contemporary art fell 70 percent during the financial rout from the peak in May 2008 when Zeng Fanzhi’s painting of Red Guards fetched HK$75.4 million in Hong Kong.

Bloomberg News

Monday, April 05, 2010

JASPER JOHNS PAINTING "FLAG"

A red, white and blue 1960-1966 Jasper Johns painting “Flag,” which once hung in Michael Crichton’s bedroom in Los Angeles, is estimated to fetch up to $15 million at Christie’s in New York on May 11. The 98 lots from the estate of the bestselling author and filmmaker are estimated to sell for as much as $75 million. Crichton, who wrote such jumbo thrillers as “Jurassic Park” died in 2008 at 66. Along with works by Picasso, David Hockney and Jeff Koons, the sale features Richard Prince, Andreas Gursky and Karen Kilimnik.

Bloomberg News

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)